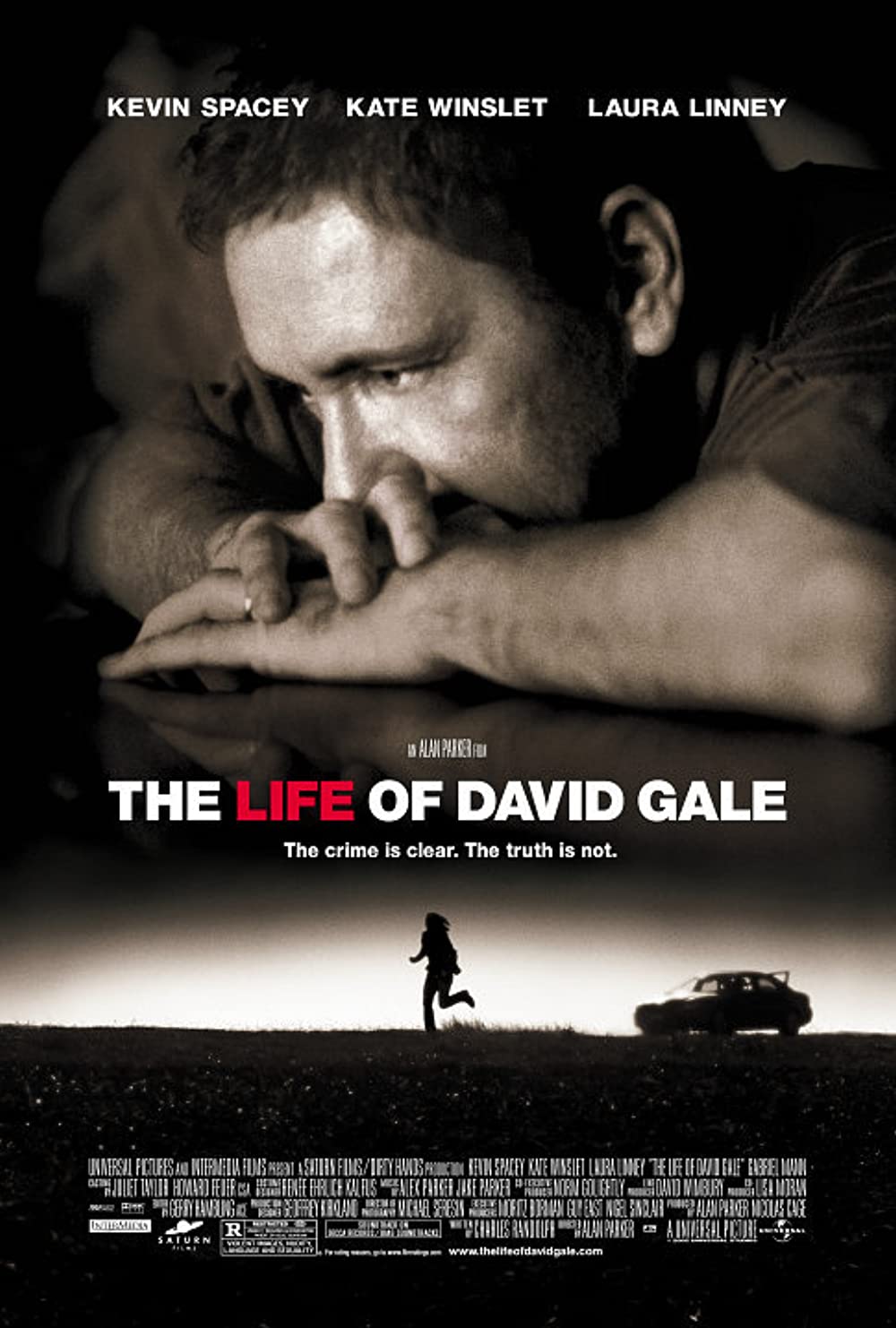

Rewatching 'The Life of David Gale' and what it can teach us about the death penalty

The conceit of Alan Parker’s movie about capital punishment is how the state committing murder on murderers isn’t just dehumanizing, it’s economically and morally costly to the community.

Ably acted by Kevin Spacey in the titular role, the theme is deployed like a police baton when Gale meets intrepid reporter Bitsey Bloom (Kate Winslet) in prison: “No one who looks through that glass sees a person. They see a crime. I'm not David Gale. I'm a murderer and a rapist...four days shy of his execution.”

Recently this 2003 movie, by the director of other flashy movies with extreme pathos as its North Star like Evita and Midnight Express, was in the news as Sen. Panfilo "Ping" Lacson said during "The Jessica Soho Presidential Interviews" that the movie had contributed in swaying him to change his views on capital punishment.

He thumbed down the death penalty when asked. He would not institute it if he were to win. Once a staunch advocate for the reinstitution of the death penalty, the candidate explained further: “Awakening sa akin iyon [Life of David Gale] e. I was awakened by the fact na pwedeng ma-execute ang taong inosente.”

There are moments where the movie just tries to prove that it’s way smarter than it really is, to thumb its nose at the bureaucrats who hold the power but cannot act morally.

There’s no shortage of Hollywood movies on capital punishment, especially about the US justice system. Benchmark ones exist in support of capital punishment like 1982’s The Executioner's Song or clearly oppose it like 1995’s Dead Man Walking. Plenty present a conflicted picture: 1967’s In Cold Blood is a good one, plus its companion movie 2005’s Capote. There’s the excellent The Green Mile (1999) and even the recent Clemency (2019), a bravura direction by Chinonye Chukwu.

In re-examining Parker’s David Gale, how has it stood up to a retrospective lens and could its narrative conceit (and twists, which there are quite a few) be powerful enough to indeed sway someone who was previously on the pro side of the fence?

Gale's story has not aged well and is nothing special. By now the intellectual who thought he could thumb his nose at authority and escape unscathed has become such a cliché that you could throw a Netflix algorithm and come back with at least a dozen movies or TV series on a beleaguered hero with decent intentions, but nearly no street smarts coming up against the most extreme punishment of the state.

A cursory look at the plot reveals a tortuously involved screenplay by then-first time screenwriter Charles Randolph centered on Gale, a do-gooder who had it all and then lost it, now behind bars. Once a devoted father and husband, a wildly successful intellectual with books to his name, the head of the philosophy department at the University of Texas at Austin, how he ended up on death row is mainly for being an activist of DeathWatch, a non-profit advocacy group campaigning against capital punishment. Strangely enough though, his downward spiral relates more to a #MeToo twist of events.

One of his graduate students (a very young and scantily dressed Rhona Mitra named, I kid you not, Berlin) seduces him at a party and the ensuing rape allegation removes his stellar reputation and motivates his wife to divorce him and take their son to Spain. But Berlin disappears from the movie altogether. Falsely accused, the charges against Gale are dropped but he’s still fired from the university because of the optics.

Eventually, he winds up selling electronics at a Radioshack knock-off, drowning his woes in alcohol. The one friend he has is Constance Harraway (Laura Linney plays her understated and with deep empathy), a fellow DeathWatch activist. How then did Harraway, the one who consoles and props him up when his life has been shredded, become a murder victim? Raped and suffocated by a plastic bag taped over her head with Gale’s semen inside her?

If as children we are taught that murder is wrong and in a Catholic country 'thou shalt not kill,' how then do we reconcile that with state-sanctioned capital punishment?

While there are several more plot twists that we won’t mention since it would truly ruin the experience for a first time viewer, suffice to say that the irony of a staunch capital punishment abolitionist sitting on Texan death row isn’t lost on us. In fact, the movie keeps nauseatingly reminding us throughout its 130 minutes.

The most interesting clincher is the point of view of journalist Elizabeth “Bitsey” Bloom (Kate Winslet). She’s been selected by Gale for a series of interviews just three days short of his execution. Gale’s lawyer has negotiated a half-million dollars exclusivity rights fee to Bloom’s magazine, and specifically for Bloom to write because we’re told that she’s gotten jail time for protecting her sources and thus has a reputation for discretion.

Throughout the plot twists we are treated to Bloom as confused skeptic and then as a believer in Gale’s innocence. So compelled, it motivates her to his side of the death penalty fence, trying everything to prove that the system has failed. Bloom as the only straight man surrounded by unreliable narrators is important in such a convoluted mystery with at least four stray threads and several head-scratching plot holes like Swiss cheese. Holes so bad not even the shlocky, surprise ending can save the day. To top it off, there are moments where the movie just tries to prove that it’s way smarter than it really is, to thumb its nose at the bureaucrats who hold the power but cannot act morally. Gale himself is that flawed intellectual who thinks himself tougher than he is, in fairness aptly depicted as someone who wanted to show that he was more clever than those in power without the tools to egress its attention.

One of the best scenes that illustrates this is when Gale goes on live TV to debate the Texas governor on the death penalty.

“Something I always say and I'm gonna keep on saying. And that is that I HATE killin'. That's why my administration is willing to kill to stop it,” said Governor Hardin.

To which Gale replies down the line that “So, basically, you feel, to choose another quote, 'a healthy society must stop at nothing to cleanse itself of evil.'”

“Well, yes. I'd have to agree. Did I say that too?” laughs Hardin.

And Gale here grins, because he’s got the politician: “No sir, that was Hitler.”

That scene is great for a laughs in the spirit of “Gotcha!” But at that point the plot is something of a preposterous albeit epic Hollywood pun on the gears of a flawed system. Considering the movie took $38 million to produce and garnered $38.9 million in profits at the box office, there’s no doubt who got the bad end of the gag.

The essence of change is abandoning something archaic or useless, for sure. The only question that remains is 'what took you so long?'

One particularly glaring plot hole (MINOR SPOILER FOLLOWS) that threatened to tumble the whole house of cards into a mess was how Gale’s family did not come home at all for the condemned man. I find it extremely hard to believe someone didn’t tell the ex-wife? On top of that, if Bloom was half the veteran journalist they portrayed her to be, why didn’t she work quotes from the “Family of Gale” angle? Really, she isn’t even going to try and contact the ex-wife and kid, maybe find someone related to him by blood? All these verification chores are entirely doable, (especially with an intern as capable as Zack Stemmons) even within a time frame of three days. I also have an issue with the revolting way the flashbacks are signaled by a spinning image of loaded words like “Desire” “Truth “Power,” imbuing this multi-million dollar production with the feel of a college project. Find better transitions, please.

While the Hannibal Lecter-Clarice Starling setup between Gale and Bloom is an intriguing proposition, the story fails to capitalize on it. Winslet and Spacey also acted their level best, but the treatment and the MacGuffins only made Spacey’s Gale come off as snobbishly sardonic. The craft of this movie is suspect, as is the surprise ending that baffled and infuriated me at such a frankly ridiculous epilogue—that scene made critic Roger Ebert quip in his review “It is shameful.”

If as children we are taught that murder is wrong and in a Catholic country “thou shalt not kill,” how then do we reconcile that with state-sanctioned capital punishment? Thereby murder is wrong, except when…?

What sways someone to change his mind over such a prickly issue of exceptions to a point where there are NO exceptions to the value of a life is always subjective—it may be true and correct that any assertion in such a change due to a piece of art leading to a path of moral decency should at least be forgivable. The essence of change is abandoning something archaic or useless, for sure. The only question that remains is “what took you so long?”

It would be more than fair to imagine that there have likely already been encounters with stories or cases that reflect or even completely mimic David Gale’s, especially in the course of one’s profession in working closely with the criminal justice system. Will he be convinced otherwise again if, say, someone gifts him with an Apple TV+ or HBO Go subscription? Though the timing may be suspect, who’s to say that being shown the light doesn’t occur while channel surfing, the Netflix algorithm suggesting more things to watch in the vein of Parker’s movie.

What's certain is plenty of potential David Gales sit in our prisons right now, as the reintroduction of the death penalty looms high.