Finding the art & soul of Hermès

I went to Singapore to view a showcase with artisans flown in from France, called “Hermès in the Making.” I wanted to see how Hermès objects are made by these artisans. And to discover some secrets, perhaps.

I ended up discovering the art and soul of Hermès.

“Secrets? There are no secrets. The secret is to remain authentic,” said Olivier Fournier, executive vice president of Hermès and president of Fondation d’Enterprise Hermès, who has been with the house for 31 years. “Since 1837, Hermès has remained faithful to its aim to be a house of objects that are designed to last and be repaired, to be used and handed down.”

Hermès has become a much coveted and much-copied brand, a status symbol that is aspirational to its followers. How do you explain the mystique behind this sixth-generation French brand with a network of 306 stores in 45 countries that employs more than 16,600 people worldwide, among whom are 5,600 craftsmen and women?

I like best the definition by artistic director Pierre-Alexis Dumas of what Hermès really is: “Hermès makes objects, garments, accessories… We do not aim for ostentation. But for something that we call ‘elegance.’ A kind of everyday politeness that makes life more pleasant, simpler, brighter.”

It was certainly this elegance, this kind of everyday politeness that drew the Tantoco family — the Philippines’ top luxury retailer — into making sure Hermès would be in the country. Stores Specialists Inc. president Anton T. Huang recently launched a bigger and tonier Hermès store in Makati in its 23rd year. Since Hermès opened here in 1999, general manager Mario Katigbak has not seen a day of quiet.

The demand for Hermès bags is loud and clear: People are willing to wait for months, even years, to have the Birkin or Kelly bag of their choice. Why does it take that long for Hermès products to be finished? Simple. These are meticulously handcrafted in France. And there are no shortcuts. That is why to the trained eye, it is easy to spot a fake Hermès.

Hermès objects are made with sustainable craftsmanship. A quest for quality, durability and innovation, a respect for the surrounding environments.

I saw this at Singapore’s iconic Marina Bay Sands, where “Hermès in the Making” was mounted with about 10 stations in four colors (orange, yellow, pink and purple) showing the intricacies of making silk scarfs, porcelain wares, bags, watches, gemstones, saddles and gloves. There were films, interactive and dexterity games, tables for coloring and creating. On display were vintage bags, Kellys, colorful scarfs, gloves, saddles, products fashioned from leather scraps, and raw materials such as silk cocoons.

Nothing is wasted or wantonly thrown away at Hermès. Godefroy de Virieu, creative director of Petith, said: “It is always materials that inspire us. For instance, metal parts like bag clasps and small crystals with defects, or even nice surprises like obsolete pommels — we see what we can do with them. Duffle coat buttons, keys to a music box. Buttons can be the top of salt shakers.”

At the National Gallery Singapore, a discussion was held between Fournier and leather craftsman Maxence Wasselin with designer Olivia Lee as moderator. They talked about their unique experiences as creatives, a bit of Hermès history, anecdotes, and corporate social responsibility. Here are excerpts:

* * *

Olivier Fournier: Respect is in the DNA of Hermès

“Luxury is defined as that which can be repaired. Every year, Hermès gets about 120,000 objects to be repaired. We encourage customers to have their Hermès objects repaired. It’s a question of respect.

“Respect for craftsmanship, respect for the environment. Respect for nature is in our DNA. There’s a strong sense of responsibility with the use of natural materials. We just can’t destroy these objects; they were made to last long and be passed from one generation to the next.

“That’s why when designers think of a new product, they should think of the way it can be used well. This is eco-conception.

“When you look at a design of a scarf, sometimes you can use the design for porcelain. That’s why we have not one, but many designers. There’s a common spirit shared. The freedom of creativity.

“We conduct workshops everywhere in France that are open to everyone who want to be artisans, regardless of age, gender and origin. As long as you are willing to work with your hands. There are no tuition fees to pay. It takes 18 months basic training for leather goods.

“When you go to a workshop and you open a bag for repair, sometimes you see coins from a faraway country, or a piece of paper that becomes precious because we learn a bit more about the customer.

“Once, we received a scarf to be repaired. It was in pieces, in bad condition. Finally we realized the scarf had been bitten by a dog. So the owner had to buy a new scarf.

“Fantastic when we put memories of craftsmen together, with objects bearing defects left behind us. The freedom of creation lets them express crazy ideas. Sometimes you can combine leather with porcelain, or porcelain with glass to create something. Like a doorstopper, for instance. This is called not recycling, but upcycling.

“We in the Foundation also bring craftsmanship to schools. We have this program of gardening where we let children take (cultivate) a piece of land without too much water. Then when they pass it on next school year to the next batch, they should be proud of it.”

* * *

Maxence Wasselin: A bagful of emotions and memories

“When we receive a bag for repair, you never know what you will get. But you know it has history. It bears traces of its past life. It’s full of emotions. Hidden emotions. Sometimes you feel you restore the emotions hidden in a bag. Life is imprinted on the object. It touches our subconscious. Like Proust’s madeleine cake.

“Artisans can also heal the soul. When you mend a bag gifted to the customer, by a mother who died seven years ago, for instance, when he touched it, it stirred a memory in him.

“One artisan got a bag for repair and then he found out it was a bag he himself made 15 years ago.

“Craftsmen put a secret stamp inside a bag to identify their works. But there was this instance when six artisans were shown six Kelly bags of the same size on the table. For me, they looked all the same. But each of the artisans was able to identify, without any mistake, which bag they made.

What is the secret behind enduring the long, complicated processes? ‘Patience. We have patience.

“That’s why handmade objects can never be done by robots. There is the sentiment of soul in a handmade object. A robot will never know this.

“When you repair something, life is regained. It takes a long time, with mindfulness. It’s like a repair of myself.

“Customers think we are magicians.”

* * *

Stories from silk scarf printers

“I am a storyteller!” was the answer that Kamel Hamadou gave when I asked him about his job at Hermès. “I tell you stories about the butterfly, the cocoon, the colors. I travel around the world.”

His fellow storyteller is Sebastian Decillis, who has been printing scarfs for Hermès for 26 years now. The scarf station was the biggest and undoubtedly the most attractive in the Hermès showcase. On the wall, you saw blue and white scarfs, and on their table, assorted designs and silk screening tools for demonstrating how a scarf is printed. I am such a scarf lover, so I stayed here the longest.

“From the design to the store, it takes two years,” explained Hamadou.”Six months for design, six months for engraving. It takes 12 months for the cocoon, the thread, the weaving, the coloration, the printing, the finishing, the washing, the stitching.”

Decillis said: “The engraving is the longest and most complicated.”

Hermès made its first scarf in 1937. It uses the traditional silk technique in Lyon, which has been the capital of silk production since the 16th century.

How does Hermès choose designs for scarfs? There are many designs from several artists, and some talents are easily spotted. “In one instance, an artist just spontaneously sent a sketch. The artistic director fell for it, invited her, and that was it!”

How a scarf turns out depends on the thickness of the silk. And how pressure is applied. “The scarf would be a little rough, so we coat it with a chemical to make it shine. The scarf loses its sheen when washed with soap and water. So please do not wash an Hermès scarf! Dry clean only!”

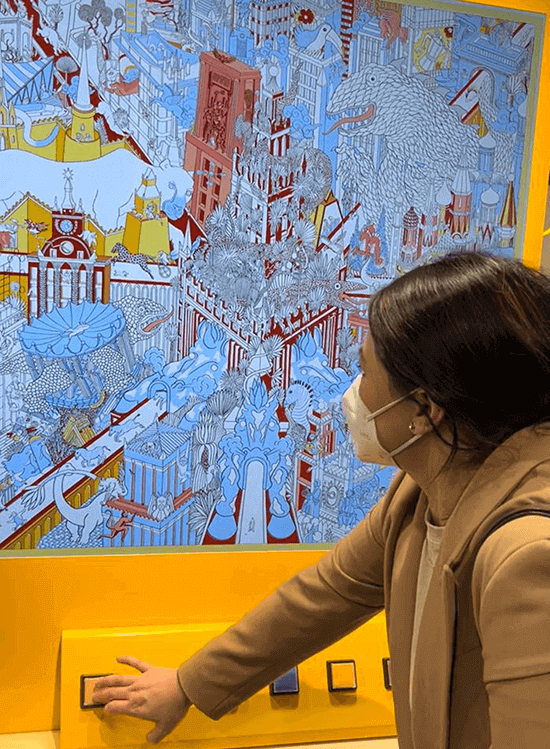

An Hermès scarf can carry many symbolisms. The silk design in the photo (foreground), as shared by Stephanie Chong, deputy general manager of Hermès Philippines, was done by award-winning Japanese artist Kohei Kyomori in 2019. “A tiger, the embodiment of courage, adorns the man’s jacket. A peony flower, the symbol of perfection, touches the turban head wrap of his companion.”

With all the complicated and long processes in each scarf, how do the scarf printers manage?

Hamadou smiled: “Patience. We have patience.”

* * *

The colorful silk road

The silk scarfs on the wall behind her were pretty, and so was Anabelle Giroud, the lady in the station for coloring.

“From the original artist’s work, a scarf design will be transmitted into engraving. I do the coloring spin of the day by colors. So for 38 colors, there are 38 layers, 38 files to be painted, 38 frames for coloring,” she said through her interpreter.

“On the average, we use 25-30 colors, and the maximum uses has been 48 colors.”

The same technique is used to produce ties and shirts, even pocket-sized silks.

* * *

So much on a porcelain plate

Painting a leopard’s spots on porcelain seems like an easy job. But it’s not. Dots incredible are made skillfully only because an artisan like Laura Many has obviously mastered her craft. It takes dexterity and the right lightness of the fingers to paint on porcelain.

How long does it take to finish a plate?

She pointed at the plate she was holding and explained: “This is a very specific blue, so it should burn at a high temperature, 1,300 degrees, and it needs six bakings, each of them lasting 16 hours.” Many added: For this one, the complete process will take around two weeks.”

Of course, it depends on the design. The outlines of the design are first done with a brush, then she fills in the colors. The vivid colors are revealed after burning in the kilns.

A Hermès manual explains that Europeans discovered that the whiteness of porcelain from China was the presence of kaolin in the paste. Kaolin deposits were discovered in Saint-Yrieix-la-Perche near Limoges, and since then, porcelain has been produced in France.

The artisan uses different brushes to faithfully capture the original design. The results are quite incredible.

Hermès really has so much talent on its plate.

* * *

Grace inside the Kelly bag

Though the Kelly bag station was small, it was one of the most popular during the Hermès event. After all, the Kelly, as well as the Birkin, is the Holy Grail of handbags.

Both bags are good investments, and their resale prices are astronomical. The Birkin is probably the priciest and most coveted. Victoria Beckham is said to have 100 Birkins, including a croc that husband David Beckham reportedly bought at $100,000. Kim Kardashian reportedly has 30 Birkins.

The Kelly bag, which initially cost $900, now commands from $10,000 to $90,000, depending on size and material. Why is it named the Kelly? The newly married Princess Grace Kelly of Monaco in 1956 famously shielded her baby bump by holding an Hermès bag. It was officially named the Kelly in 1977.

Lest bag lovers forget, the Kelly was inspired by its equestrian predecessor, the Haut a Courroies, first conceived in 1892 for carrying riding equipment. There are several types of Kelly bags, including the Sac a Depeches introduced in 1935 to hold documents. Famous stylish users of this bag included the Duke of Windsor and John F. Kennedy.

Seen at the Kelly station was the Kelly Picnic, using wicker. Did we imagine the Kellywood in vibrant colors? The Kelly comes in the more formal Sellier, and the more relaxed Retourne, which we saw.

Artisan Anne Hauser showed the bag inside and out to show the precision with which the bags are made with saddle stitches, which can be between 680 to 2,600, depending on the size, which comes in 25, 28, 32, 35 and 40 (cm., based on the width of the base). Micro Kellys are 15 and 20, while the larger ones are 42 and 50.

Why saddle stitches? Remember that Hermès started as a maker of harnesses for horses. An artisan takes about 18-24 hours to put together up to 36 leather pieces into a Kelly bag. A handle alone can take three hours to make. Training for an artisan to be a bag maker is at least a year.

Do bag makers develop calluses on their fingers? The artisan simply put her hands on her chest, as if saying, “I work with my heart.”

* * *

Galloping into the future

If you want to have an Hermès saddle repaired, there is a book where Hermès has the stories of all saddles it has done, each one numbered. This is according to Fournier, who adds, “Saddles made 20, 30, even 100 years ago are listed here.”

Hermès, after all, started as a harness maker. “Giving painterly representations of the gallop was a real issue in the 19th century,” a writeup on Hermès says. No wonder its logo is a horse-drawn carriage. And remember those symbolic little horse charms hanging from Hermès bags?

Saddle-making is certainly an expertise of Hermès, says artisan Helene Rolland, who explains the techniques that make an Hermès saddle durable and comfortable for equestrian disciplines such as jumping, dressage and cross country.

“The leather pieces are assembled on a central saddle tree made of wood, which is then hammered into place using nails cast from a single piece of metal for optimal resistance. The seat, panels and flaps are lined, shaped, and then sawn using saddle stitches, and are designed to be light so as to bring a sense of closeness between rider and horse.”

Made in partnership with award-winning equestrians, Hermès uses new materials and technology with its traditional techniques. That’s how Hermès gallops into the future.

* * *

It fits like a glove

“It takes a week to customize a glove for you,” says Jean-Pierre Paillot at the glove-making booth.

And may I say: But it took ages for Hermès to develop this expertise so that you can say if it’s by Hermès, “it fits like a glove.”

The tradition of glove-making traces its roots to the Middle Ages in the Limousin region, where Hermès was recognized as a Living Heritage Company in France.

Glove-making may seem deceptively simple, it is said, but “22 steps are needed to finish a glove.” The procedure is explained thus: “The glove-maker assesses the quality of the hides. The inner flesh is softened using a sponge and the outer grain is powdered using talc. The leather is then stretched and pulled to ensure that the glove will keep its shape and suppleness…The iron-hand shape cutter, invented in the 19th century, is then used to cut the exact shape for each finger. After they are hand-sewn, the gloves are slipped into a “hot hand” iron for the final touch of elegance.

Now, that is really hot.

* * *

Watching Hermès

The first Hermès watch was made in 1912 by patriarch Emile Hermès, who attached leather straps to a pocket watch so that his daughter Jacqueline would wear it around her wrist.

When I bought an Hermès watch at the San Francisco airport’s Duty Free shop many years ago, even before Hermès opened in Manila, I did choose the one with long brown leather strap to go around my wrist, because I thought it looked unique. My watch still works perfectly fine, and I believe the next generation will still be using it.

So what gives longevity to a classic watch? What happened in the watchmaking station? The meticulous work of assembling the Hermès H08 timepiece was shown by expert Massimo Pagliari, who has 30 years of experience behind him.

How does a watchmaker work? “Using his left eye, which is focused on the magnifying loupe, the watchmaker lays out the static components onto the disc of the watch. The gear train is then delicately calibrated to create the mechanical movement that helps the watch keep time… Plate, bridges, trains, barrel, balance — these are the delicate elements within the confined case of a timepiece.”

It is always time for excellence at Hermès.

* * *

Last but not least

“There are many traditions everywhere and we should respect these, because it’s all part of our heritage,” said Fournier.

So I asked him: Through the years, Hermès has been inspired by the bamboo of Japan, the lacquerware of Vietnam, and the cashmere of Mongolia. Has Hermès found any material for inspiration from the Philippines?

“No,” Fournier answered.

“Not yet.”

* * *

Following its success in Copenhagen last year, the traveling showcase “Hermès in the Making” has made stops in countries like Italy and the United States. After Singapore, it continues its world tour in Austin, Texas. It will go to Kyoto, Japan, in late October.

* * *

In the Philippines, the Hermès store is in Greenbelt 3, Ayala Center, Makati.