Walking through the tasty history of Singapore’s Chinatown

I called it revenge vacation.

For two years my wife and I had foregone our yearly tradition of traveling somewhere, anywhere due to COVID restrictions (and fear of catching the plague). So when the chance came to fly sans visa to Singapore for an event, and also to simply get out of the chaos of Metro Manila, we planned out a trip that scrimped on accommodations but was indulgent on everything else.

On that “indulgence list” of a stay for five days in early June 2022 was a food tour. It was billed as private and immersive.

Though I’d only been to Singapore once, one of the few things that intrigued me was the food, diverse and yet almost familiar to Pinoy taste buds and how those cuisines carried with them what must be the heritage of a time when the country was less planned urbanity, more bedlam of developing trade hub just out from under colonial rule.

Among Singapore’s hallmarks to economic success was the desire to attract foreign capital. Plus, an implicit understanding that free trade was good for everyone. It’s an endpoint that Anthony Bourdain dubbed “A utopian city-state, run like a multinational company.”

This process of taking Singapore from a Third World outpost to a First World nation within a single generation could be traced as well to the ubiquitous hawker centers. Now this I was deeply interested in.

To find out more, and to eat our way through an education of stories, we hooked up with tour guide Leonard “Leo” Loo. We met Leo at the Chinatown MRT Station on new Bridge Road to begin revenge vacation in earnest, making sure I had downed an anti-histamine the night previous, since I suffered from allergies to crustaceans—I was never worried though, since my wife could devour anything I could only nibble.

Breakfast was at 9AM. Soft boiled egg with Kaya Toast and coffee at Hong Lim Market & Food Centre at Upper Cross St. A classic with coffee or tea that the Hainanese immigrants had created, adapting meals served on British ships docked at ports back during the Straits Settlements period.

As far as tour guides went, Leo was one of the best. Walking along with him for almost five hours in Chinatown was a pleasure, experiencing something more than a tour through a veteran, English-adept guide.

Beyond history, Leo shared personal moments. Beyond food, Leo shared culture. And he took it further to foster a connection of shared stories. Something you wouldn't get with a bigger group tour or even with a less experienced or less English-adept guide.

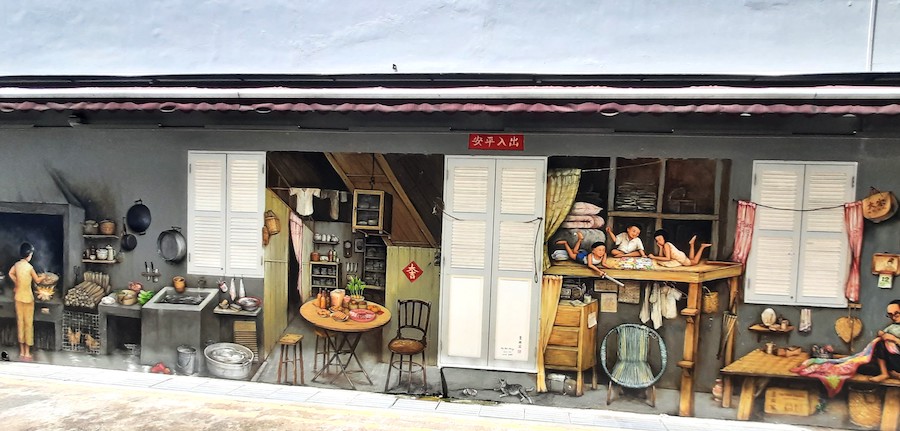

I’d explained to him that what we were after was both food and the stories about the cuisine. As we walked through the street art and the bronze statues depicting Chinatown’s old life—like the woman Peranakan merchant and the rickshaw puller of Lim Leon Seng’s “Heading Home” on China Square Central ala our 1800s Facundo and Senyora—Leo told us how he had been an accountant when he was young, working in finance and consulting until he retired.

In a year of transition, he recalled how he feared becoming a cleaner or a cook in the hawker centers we were heading to, eventually reinventing himself as a tour guide with both a walking tour and a bike tour. He’s now 59 and runs Tour About Singapore almost entirely solo.

The man emphasized interesting points tailored to what we wanted to know. Along with food trivia of how the current hawker centers were once food carts and street stalls that the government had to overhaul because they’d developed into magnets for vermin with leftover filth and kitchen refuse, he shared how much even a hint of corruption is avoided in government employees, even a tour guide like himself, so the best way to tip him was through a good review.

Along with lessons on Singlish (“Why liddat?!”), what “No Touting” meant (this omnipresent sign at hawker centers means it’s illegal to coerce people to buy your food or services or to be too agro in selling ala our Divisoria tinderos), and how to reserve a preferred table by using “chope” (leave a tissue pack or a bag on a table to indicate someone is already there and folks will respect that), Leo took us through the history of Chinatown.

Way back in 1822, under British rule, Stamford Raffles set up a trading settlement system where the city was segregated according to four ethnicities. And the Chinese got the area near the Singapore River, giving birth to the foundations of current Chinatown. As we walked through the wide corridors of what used to be the horse cart lanes of Old Chinatown, since converted to a prime spot for hipster restaurants and bars, I observed how the heritage buildings retained their old shophouse frontage architecture and window shutters.

Leo pointed out, later in some dioramas, the small hinged trap doors in each structure where arinolas of the families were collected every morning by hired night soil men—the sewage and refuse folks of yore. When the waterfront was eventually reclaimed, some of the local temples remained, even the one to the river goddess though the nearest body of water was now a few miles away.

With Singapore hawker food since added to the country’s UNESCO's intangible heritage list the mix of Chinese, Malay, Indian, and other cuisines that made up the local food palette gave me a deeper understanding about the amalgam of local cultures.

We spent brunch at J2 Famous Crispy Curry Puff at Amoy Street Food Centre on Maxwell Road. Run by a single family, Lee Meng Li and his wife Wu Jing Hua used to manage a bakery. But that business quickly closed shop because of a spike in production costs. To bounce back, the couple learned how to make an excellent curry puff from one of their relatives in the restaurant industry.

Since opening J2 in 2007, their puffs (a choice of curried potatoes which was the one we had, sardines, yam, or black pepper chicken) became sought after with recognition from the Michelin Guide to boot and daily long queues. Even if they are now joined by their children at the stall, they can only make 500 curry puffs a day so quality is sustained. Working 14 to 16 hours a day with only one day a week off isn’t so bad when you have a payoff of a few million and a Michelin mention of approval.

For lunch we were taken to Tian Tian Hainanese Chicken Rice at Maxwell Food Center on Kadayanallur St. A famous stall where Madam Foo Kui Lian, in July 6, 2013, beat celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay at the SingTel Hawker Heroes Challenge. They were also awarded the Michelin Bib Gourmand Singapore in 2016 and 2017. Aside from the refrigerated whole buko I got from another stall to down this meal, this was my favorite because of the fluffy, fragrant rice and excellent, tender chicken. A wonder of minimalist tastiness. Little wonder it’s hugely popular with locals and tourists.

Maxwell Food Center was walking distance from the Chinatown MRT station and, from the number of salarymen at the place for lunch, also one of the best local places to try out the heritage dishes without burning a hole in your wallet—though often generous in servings, you can easily fall for overpriced food in Singapore, with some items going up to SG$8. But at Maxwell, dishes can go as low as SG$3. Unlike other hawker centers, some stalls here are also open until 10pm.

Since the median age of hawker cooks in Singapore is 59 years old, there have been efforts to incentivize younger generations to take up the family business, even if the preferred career arc for young Singaporeans is still a nine to five job in an air-conditioned office.

The fact that locals can also hire only Singaporeans or permanent residents as assistants at hawker stalls add to the manpower dilemma, especially when the next generation refuse to take up their grandparents’ or parents’ frying pans.

After a Fuzho oyster cake that (which Bourdain ate on one of his CNN episodes), we headed for desert to Old Amoy Chendol at Chinatown Complex on Smith Street. The chendol is a sweet iced dessert like the Korean bingsu. At Old Amoy, their chendol is very fine shaved ice, topped with fragrant gula Melaka (palm sugar), silky coconut milk, a spoonful of red beans, and handmade pandan flavored jelly. Everything is prepared fresh from scratch daily. This recipe is of course presented differently depending on the hawker stall, but is almost universally prized as a snack for hot days in such an equatorial location. In Singapore, temperatures in the shade can go up to a dry 32 degrees Celsius for months during summer.

After a quick museum tour at the Singapore City Gallery (where highly detailed dioramas of old Chinatown and interactive multimedia presentations displayed the various government projects for reclamation, accomplished and forthcoming), we ended the tour at the same hawker center, eating Curry Chicken Noodle Soup to see us through merienda and the rest of the day at around 3pm.

There were only two of us for the whole tour and at a cost of SG$150 (around P5,900) the food and the stories were definitely worth the almost five hours of walking. Though the final meal could have used tweaking—instead of the noodle soup we could have used a replacement of desert (as Pinoys commonly like a sweet snack for merienda)—the increasing heaviness of the food items was pretty spot on and delivered obviously after much trial and error.

In a country that’s big on food culture, hawker centers housing more than 6,000 stalls are crucial. A guide to the ones most worth your time and money is just invaluable. Someone who can curate stories in articulate English with the cuisines is definitely an added bonus.

Connect with Tour About Singapore on IG.